get used to it man thats the way we live now

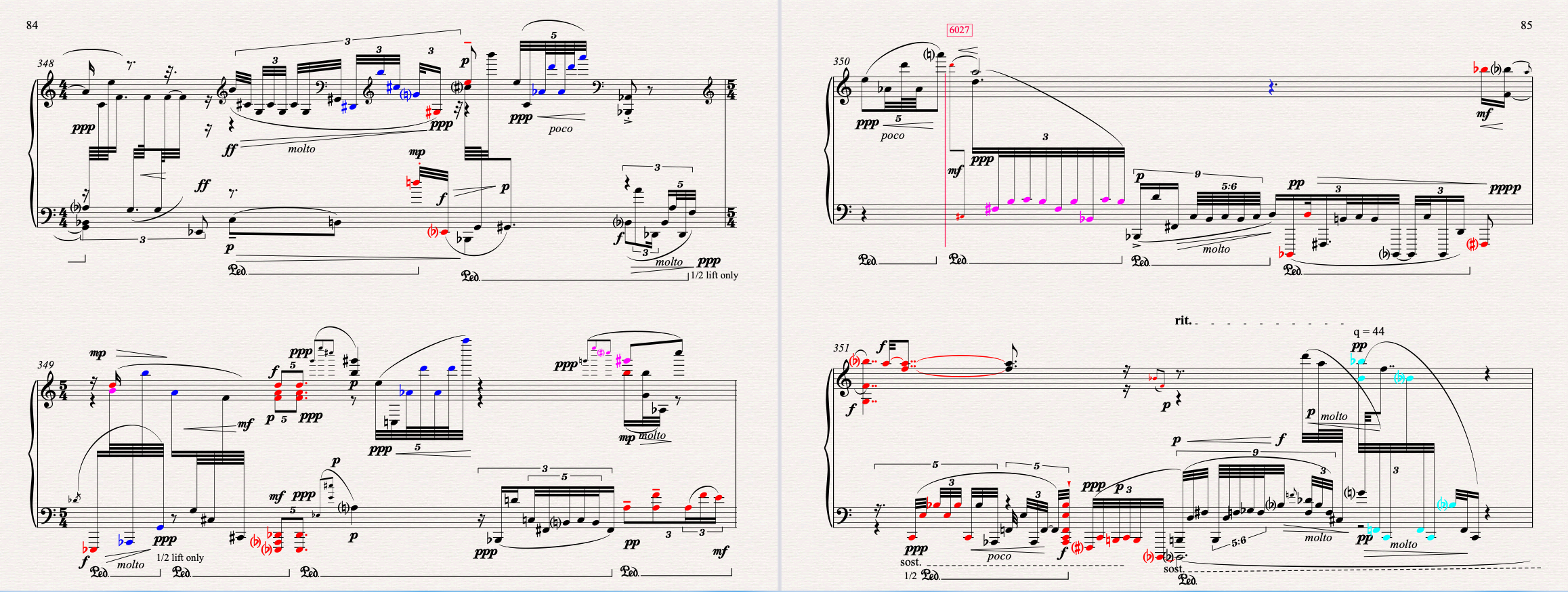

Our current project is get used to it man thats the way we live now, a work for piano by Matthias Kriesberg with live electronics by Kevin Larke.

get used to it man thats the way we live now

Employing Steinway's Spirio technology in unprecedented ways, the piece represents our approach to real-time sound transformation revealed through virtuosic performance.

Spirio technology is at its core a very sophisticated player piano with a perfect memory. It captures every keystroke and nuance so that it can "replay" exactly what and how the live pianist performed. At Currawong we extend this technology beyond simple recording and playback to include real-time performance analysis based on the raw data provided by the Spirio sensors.

As pianists interpret the score in the traditional role of pianist at keyboard, an array of speakers produce electronically generated sound that is entirely derived by innovative transformations of piano sound, effectively extending the piano's sonic world.

get used to it man thats the way we live now

get used to it man thats the way we live now

Our computer not only generates sound but simultaneously analyzes the pianist's performance in real time. These analyses further shape the electronic sound transforms.

The piece is designed to be realized in several versions, and by a number of pianists. One realization is for live concert performance employing five soloists, the other as an "Installation / Performance" using 15 soloists, suitable for a multimedia museum exhibit.

In both versions each performer is assigned a unique set of fragments to play over the course of the piece.

get used to it man thats the way we live now

Accordingly the computer is not only analyzing an individual performance as compared to the score, but as compared with how the other pianists in the mix perform their sections.

Intro2

The piece maintains a growing history of its performances. The computer doesn't just compare one performance in real time against another. It also analyzes a given rendition against earlier ones. Each recorded performance is perpetually available as a source of comparative data for later performances.

More about the piece:

More about the music