get used to it man thats the way we live now

Score and Sound

Score and Sound

Download the score or listen to recordings of the piece.

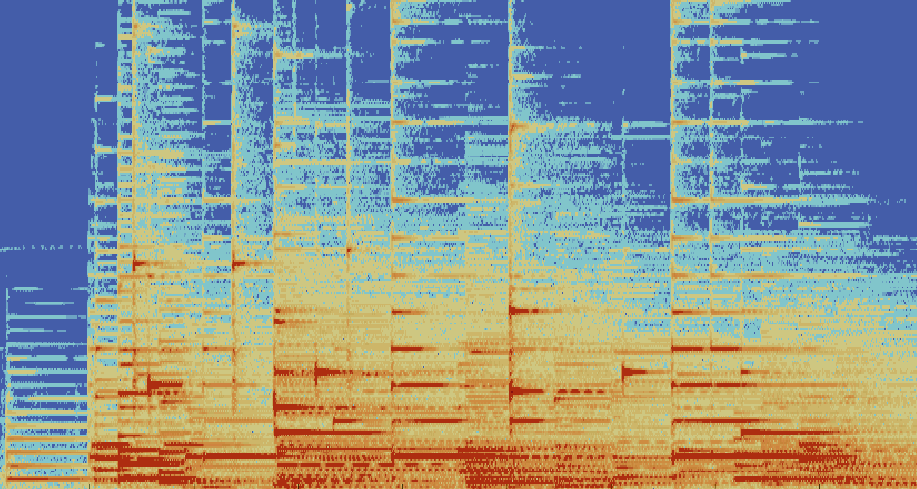

Audio: Download or listen

Score: Installation / Performance

1. Standard black / white score with ottava.

Use for learning the music, recording and performance.

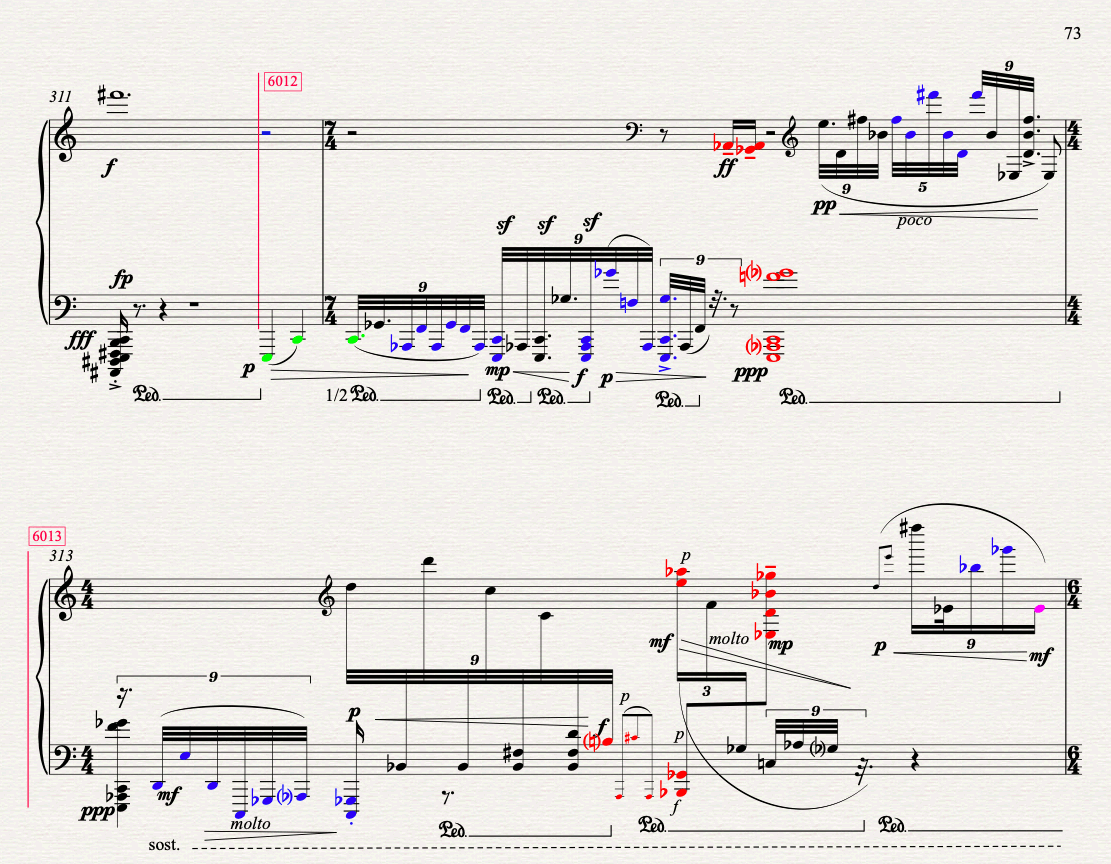

2. Fifteen assignments shown with colors. This version of the score is useful to easily identify the assignment each pianist will uniquely record and to generate an audio rendition of the score with Sibelius.

Ledger lines, no ottava.

Each assignment consists of six sections, thus the 15 colors used to represent 15 pianists / 15 assignments each appear six times in the score. To view any one of the 15, scroll through the score noting the specific color associated with that assignment.

Order of appearance, along with the 6-digit color code and starting fragment identifier.

Part 1

Part 2

Score: Concert Version

1. Standard black / white score with ottava.

2. Standard black / white score without ottava.

This version of the score is useful to generate an audio rendition of the score with Sibelius.

3. Five assignments shown with colors

With ottava.

Ledger lines, no ottava.

Concert Version

Concert Version

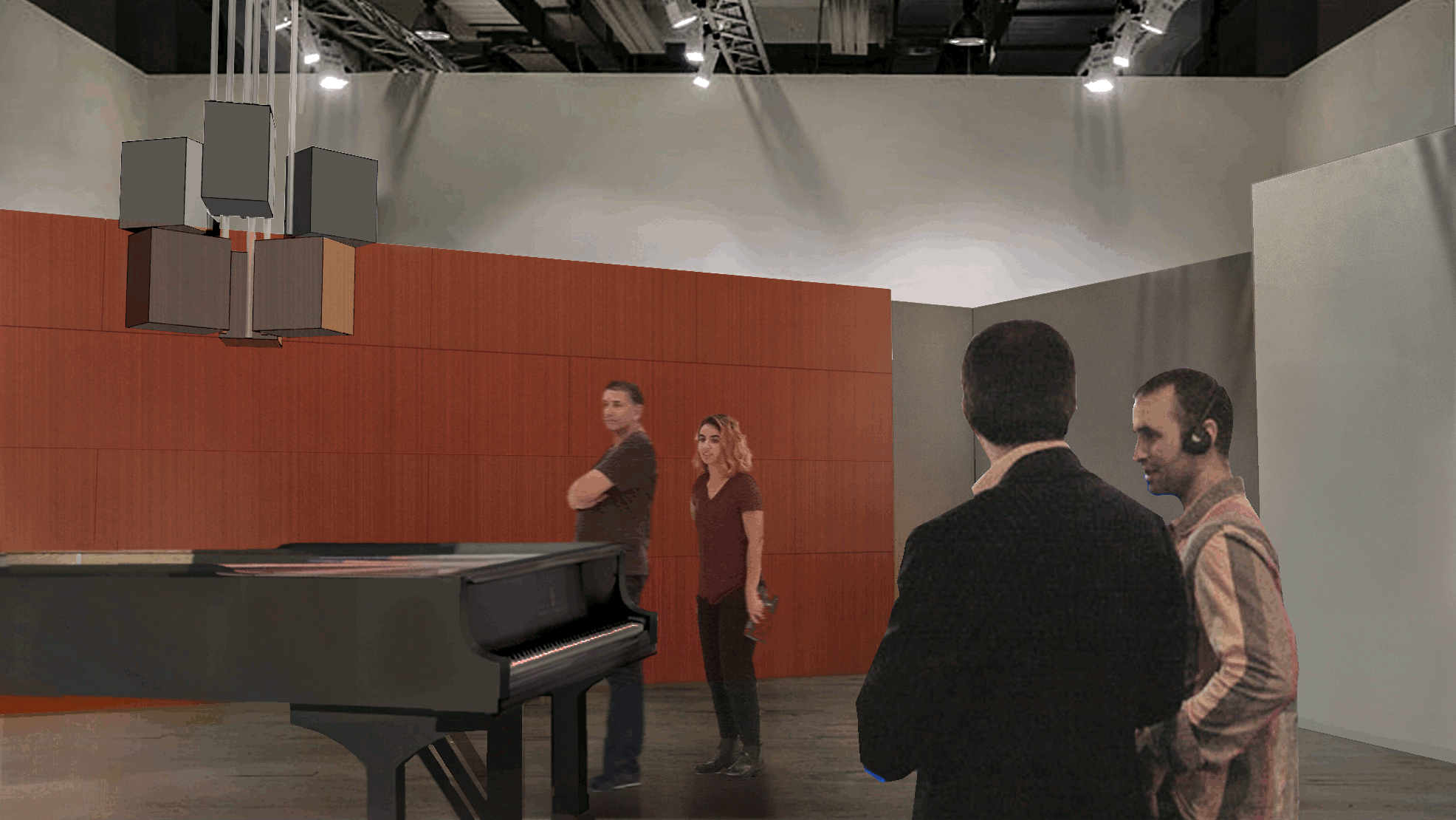

The piece is presented by five pianists on three Steinway concert grand (model "D") pianos. Ideally -- but not a requirement -- one of these will be a Spirio (see below). The three pianos need not be close together, but the layout should be symmetrical such that the distance between any two is about the same.

Also required: A high quality sound system with four or eight speakers, or other site-specific array, to transmit the electronically generated sound that is responsive to the performers' interpretations.

Why five pianists? There are a number of reasons, the most vital one intrinsic to our musical practice that applies comparative performance analysis to sound transformation. This unfolds both in real time and drawing from an ever evolving performance history. In these concert versions we analyze how all five virtuosi manage the music they perform -- in contrast to one another, and to their own evolving performance histories. All of which is realized through the electronic sound transformations heard along with the music played at the keyboards. Every performance is thus a work in constant transformation, with no two performances of the work, including the electronics, ever being the same.

Why three pianos? The reasons are both logistical and spatial. The piece is comprised of 90 sections of an average 25 seconds in duration, from which each pianist is assigned 18. These are distributed over the course of the entire work, so that practically all five artists are seamlessly realizing the entire piece from start to finish. Logistically, this requires at least three pianos, so that one is active, one is on deck with the next pianist ready, and one is awaiting an upcoming pianist to take a seat.

The result of this arrangement is an ongoing spatial interplay of piano sound, plus the constant (but always calm) motion of pianists quietly making their way from one instrument to another.

The program:

The work is performed twice, with an intermission between. During the first performance, there are 10 "attacca" interpolations of short pieces by Scriabin. Each pianist plays two of the 10, the pieces enter and depart within the prevailing texture of get used to it man abruptly, so that during all 20 transition moments (10 entrances and 10 exits) it may not always be immediately apparent which music is which. The total duration of uninterrupted music from start to finish in the first half is approximately 51 minutes.

The second performance of get used to it man will be uninterrupted, and preceded by a single, somewhat longer Scriabin work, e.g. a Sonata.

The nature of our practice of dynamic music is such that the electronics in the second half of the program will be markedly different from the first half, as they are shaped by performance history captured during the previous performance.

During the entire concert the audience is encouraged to be mobile. Seating is of course provided for all, but attendees should feel free to take advantage of the opportunity to observe and listen from different vantages.

Composer notes on the Scriabin interpolations:

Looking back at the history of Western concert music, we find periods of relative stability, with a certain critical mass of composers (the ones we know best) working within a measure of stylistic agreement. At other times a common aesthetic was thrown open to question, with the prevailing sentiment being a commitment to disruption. Eventually another practice would take hold that attracted enough composers such that a new plateau came to the fore.

It is those moments of instability, of reaching out for something not yet known, that resonate most strongly with me. I find some of the most fascinating and promising music ever composed to be from the first few decades of the 20th century. Tonality as an overriding principle was no longer presumed, yet no one had established any definitive, agreed organizing principle -- at least none that more than one composer could subscribe to. When we hear music from that period of uncertainty, of transition, it still seems to be full of promise. The directions music eventually followed are not, to my mind, the most satisfying nor were they inevitable.

The late piano works of Alexander Scriabin are to my ear bright, shining examples of an exploration of what, a little more than 100 years ago, a new aesthetic might sound like. It's no accident that these works are short -- they are arguably expositions without the possibility of development. In an effort to make the synergy between these works and my own musical interests more apparent, we hit upon what we hope listeners will find an intriguing presentation: Over the course of my 38-minute piece, periodically interpolating -- attacca, without warning -- 10 highly succinct Scriabin works.

All of the pianists participating have, safe to say, their own affinity and performance history with Scriabin's music. I hope therefore that the immediate proximity of Scriabin's abstract works to my piece in this presentation design might further inform their performances of my score.

Installation / Performance

Install Version

Fifteen pianists are engaged to realize the complete piece, which is intended to be realized on a Steinway Spirio concert grand in any number of locations for a defined period of time, as is customary for a museum or gallery exhibition.

How it works: The piece is comprised of 90 sections of about 25 seconds in duration, from which each pianist is assigned 6 to record and upload to the Currawong platform. The total amount of music each pianist learns and uploads is about two-and-a-half minutes.

During the recording session, pianists will upload numerous takes of their unique set of six fragments. We expect something on the order of 8 - 10 uploaded versions of each fragment to populate the source queues.

All pianists are encouraged to refresh their queue with more uploaded recordings from time to time. On an ongoing basis we will listen to new versions and accordingly update the queues as warranted.

Pianists may also learn, record and upload additional fragments, so that what was initially one pianist / one fragment queues become populated by more pianists. The result will be that Installation / Performance realizations over time will present ever increasing variance.

Let's try to explain that one by getting into more detail about the digital sound transformations. At a primary level, transforms are pre-set in the sense that the general type of transformation is selected in advance for every phrase. Then at a secondary level the transforms are shaped -- "fine tuned" -- by how a preceding passage was played. As the piece progresses, the computer is not only modulating piano sound, but also continually evaluating characteristics of the performance. As more pianists "weigh in" by uploading their performances of more of the many available fragments, the overall variability of these performed fragments will increase. Accordingly the overall spectrum of sound transformation over time will enlarge as well.

Accordingly there can be no "definitive" version of any fragment, let alone the piece itself. Note: The order of fragments within the piece itself never changes. This is a piece composed from beginning to end and the score is the score.

Concert Preview

Concert Preview

On November 5, 2025 three pianists -- Han Chen, Arseniy Gusev and Nicolas Namoradze -- recorded excerpts from the piece using two pianos. Video artist Huei Lin at left.

Watch excerpts of get used to it thats the way we live now.

The downloadable audio file below presents sections from this recording, including our dynamic transforms, and with three Scriabin pieces interpolated attacca within. (The full concert performance will interpolate ten brief Scriabin works.) They appear in the following order:

- 1. Excerpt from Sonata #10 Op. 70 (Namoradze)

- 2. Prelude Op. 51 #2 (Gusev)

- 3. Prelude Op. 74 #5 (Han)

- Notes:

- The full concert version is scored for five pianists, three pianos.

- On occasion passages in this recording are performed not by any of the above pianists but via Steinway's Spirio technology, capable of realizing a score directly.

- Total duration: 15 minutes.

- Please be careful when listening through headphones, as the dynamic spectrum is quite wide. We advise starting at a low volume and increasing carefully to a comfortable level. The first dynamic transform, 16 seconds in, is one of the loudest moments.

Composer Notes

Composer Notes

get used to it man that's the way we live now is in two parts, written at widely separated times: Part one in 1986, part two in 2018 - 19. The common link is that they are both interpretations of the same "sketch" - somewhat as if an artist returned to the same landscape many years later to paint another interpretation of the view.

Beyond that... Well, I'm a skeptic about whether anything composers write about their own music is ultimately illuminating. So I'll try to be brief.

The thing I want to do in any piece for a soloist is to gain as much purchase as I can on the full range of expression the instrument offers. And there is nothing up for that challenge like the piano.

Let's try to tackle the interesting question about musical language itself. I will back into an answer this way: No matter how complex the moment, no matter how much is going on in a measure, I want a listener never to lose a sense of "place" at any moment. I don't mean grounding at all in the sense of traditional harmony, yet something not totally at odds either - rather the goal is a certain balance between dreamlike imagination and a sense of stability that I hope is present but hard to pin down.

All very nice, but how to achieve? When I think about the time we roughly identify as Modern to Contemporary, the past 75 years or so, the works that strike me as the most glorious achievements were not products of various "movement solutions" (e.g. serialism, new romanticism, minimalism) but rather from the cracks, as it were. With feet planted in more than one space -- hybrids, arguably.

I'm sure there are many great pieces out there I have not been fortunate enough to hear. A few I have been privileged to write about, such as Nono's Promoteo and Grisey's Les Espaces Acoustiques and Schnittke's string quartets. The fact that these pieces are as breathtakingly great as they are proves that music that speaks largely in the realm of the abstract can be just as emotionally and intellectually powerful as the most revered works in the classical music canon.

A composer can't credibly proclaim "I achieved this" but can fairly say "this is what I tried to do". So let me point to two short piano pieces by Stefan Wolpe, Form (1959) and Form IV (1969) that were of singular influence on my development of a musical vocabulary. (With the caveat that when you are any kind of artist in your teens and early twenties -- as I was when I first heard these pieces -- anything you really like becomes influential.) In a sense -- I realized this only in retrospect -- the two parts of get used to it man are, in relationship to each other, something like between Form and Form IV.

If I may add this about Wolpe: The few pieces he managed to write in his last years, perhaps at moments when the cloud of advanced Parkinson's disease that he suffered from had briefly lifted, are to me among the most profound accomplishments of music from that era. The time period is around 1969 - 1971. They are not lengthy or complex -- rather, they are gossamer and concise, almost fragile. But they point to a path forward.

What about the electronics? Elsewhere on the site there's plenty of detail on that, so here I'll try to say what they mean to me compositionally. First, the piece is perfectly OK on its own; it doesn't "need" the electronics. I try to push the envelope as to what the piano -- and the pianist -- can achieve. The electronics are meant as (1) a kind of inevitable extension of imagination (as in, how weird can things get and yet retain a constant sense of place); (2) a repository of the history of interpretation and performance that in turn shapes future performances -- something that we could only contemplate very recently. An essential aspect of composing in this medium is that the electronic transformations will never be the same twice. They can't be, because they are informed by how the piece is played during each never-to-be-repeated performance, and further derive from shaping a passage in performance by comparison with how others played the same passage at other times.

Back to Wolpe for a moment more: My first years as a student at Columbia coincided with Wolpe's last years with us. His music was prominent at new music concerts, and so I would see him in the audience. There was one moment -- just one -- when we actually crossed paths. We were both living at Westbeth in the West Village. I was entering the building as he was being carefully wheeled in. He looked warily over his left shoulder at me, and I nodded, no doubt imagining to myself that he recognized me from the audience. I said nothing, of course. Looking back how I wish -- hindsight is easy, right? -- that I had said something like... "Oh Mr. Wolpe, your music means so much to me!"